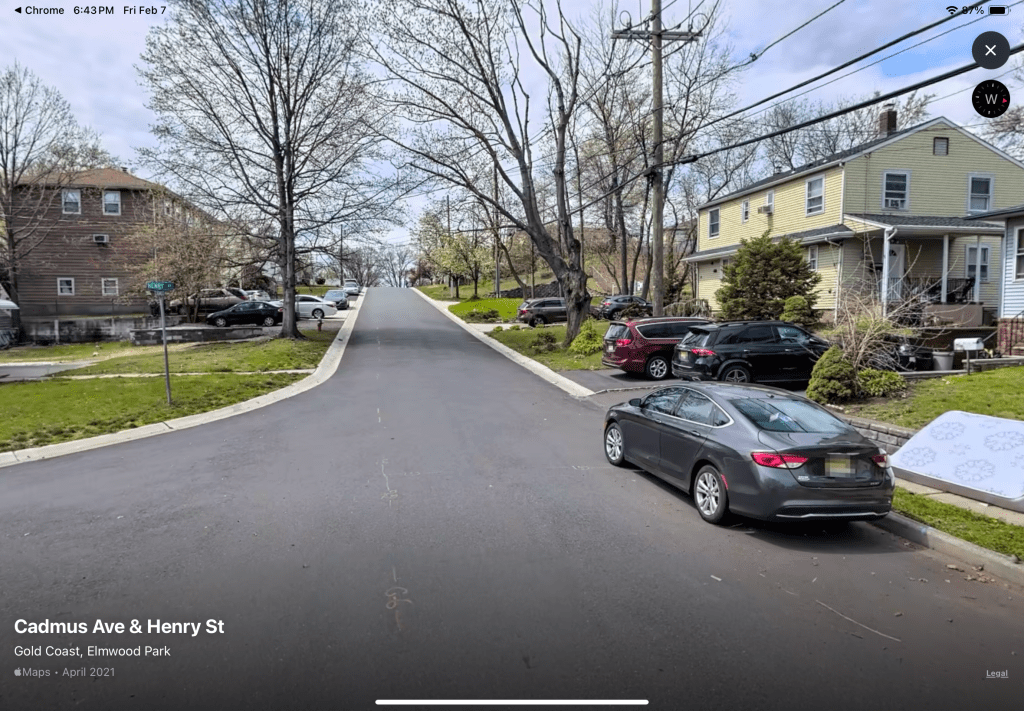

The photo above was used as the prompt for the Chatham Writers Group. It reminded me of the trip Barb and I took through the southwest and the sites we saw along Route 285 between Carlsbad and Santa Fe, then along sections of old Route 66 to Flagstaff. With that in mind, I wrote this piece of speculative fiction.

Red’s Cafe

On most days that it wasn’t raining or too cold, Pete and Lenny would shuffle out to the area called “the courtyard” and lay claim to two faded green plastic garden chairs to watch the sun set. As dusk fell, the art deco lights atop the building behind them would first hum then burst into brilliant white block letters noting “DOTTIE’S SENIOR LIVING”. Except for the letter “I” in senior. That had burned out a long time ago. Pete would chide Dottie’s manager 3 or 4 times a week. “Damn, it Reggie! Tell Dottie to fix that I. That’s why the men outnumber the women three to one in this place. People read that as Señor Living and think that it’s just old fart men living here.”

They settled into their chairs, each gripping a plastic cup, 2/3 full of Coke. They waited until a group of residents accompanied by a few nurse’s aides trudged past them to smoke in the parking lot of the Evangelical church, generally referred to as St. Nicotine’s, next to Dottie’s, because Dottie didn’t allow smoking on her property.

When the coast was clear, Pete pulled a pint of Myer’s Rum from the inside pocket of jacket and said, “Here Lenny. Let me top off your Coke.” They tapped their cups, said “cheers” and sipped until the sun settled out of sight.

Lenny stood, placed his hand on Pete’s shoulder and said, “I’ll grab us a couple more Coke’s. There’s something I need to tell you, and you’re gonna need a stronger drink.”

Pete’s eyebrows raised, “What’s this about, Lenny?”

“Be right back,” was all he said.

When he returned, Pete was leaning forward in his seat. Lines of concern added to the creases in his brow.

“I’m going to tell you a story. It’s true. I hope you don’t think I’m nuts. The only other person who’s heard this was my wife, rest her soul. It really happened.”

Inwardly, Pete was relieved. For a moment he thought Lenny was going to tell him he was dying. “Go ahead, my friend. Now I’m intrigued,” was all he said.

“Okay. But no laughing! Remember that TV show, Route 66? Those two guys driving from Chicago to LA in a Vette?”

“Yes.”

“After I graduated from college, I did that. Started the summer driving Route 66 before getting a real job.”

“In a Vette? You dog Lenny! You never told me.” Pete looked wistful.

“No, sadly. In my dad’s 1960 Chevy Bel Air. Not a cool car, but a cool trip.”

“Yes! You lucky dog. I would have driven it in an Edsel.”

“Yeah. Well, what I am going to tell you next, Pete, is I don’t know if this was truly luck. Or something even bigger.”

“Okay.”

“I was going to stay in Holbrook, Arizona. A place called the Luna Moth Motel. I even made a reservation.”

“The Luna Moth? You’re joking right? This I gotta hear!” Pete took a sip of his drink and leaned forward, grinning.

“It’s not what you think. I’m driving on Route 66; the country is so flat. Three miles out of Holbrook. I see the lights and buildings at the edge of town. Good thing, ‘cause I was tired from driving all day and was pinching myself to stay awake.”

“Been there,” Pete said.

“Now the strange stuff begins, Pete. There’s a Cities Service station on the right side of the road. It looks abandoned. Only one pump where there used to be four. Signs faded and peeled. It had been called ‘Red’s Café and Auto Service. The only clear word was Café.”

“Go on,” said Pete.

“I’m about to cruise past and this old guy steps out from behind the only pump and waves at me like crazy. Motioning and yelling for me to pull in. He looked upset, so I brake hard and cut into the gas station’s driveway.”

“How old was the guy, Lenny? We’re old!” laughed Pete.

Lenny smiled and nodded, “Yeah, Pete. About how old we are now. His Cities Service uniform had faded to almost turquoise in color. Except for his name tag, it’s still bright green and in bright white cursive letters in the name ‘Red’.”

Lenny paused for a few moments, as though trying to remember. Softly, Pete asked, “What was up with Red?”

“Well, he asked me to help find a set of keys he dropped in the sage brush behind the station. He said his dog was locked in the office, and he needed to get him out. I agreed to help, but all the time we were looking, I didn’t hear a dog barking.”

“Were you worried it was a trick? That he was going to rob you. Or worse?”

“Yeah, a little. Anyway, 20 minutes later we still haven’t found the keys, and we’re back in front of the station. He stops and points towards the town and he says ‘look’. ‘At what?’ I ask. Suddenly there’s a bright flash, flames shoot out sideways and skyward. Three seconds later we hear the loud boom.”

“Fireworks?” asks Pete.

“No!” exclaims Lenny. “The old guy says, ‘Well, looks like the Luna Moth Motel just blew up. I guess they never did figure out where the gas leak was. Weren’t you supposed to be staying there? If I were you, I’d try the Wig Wam Motel, nicer place too.’”

“What happened next?”

“I turned to look at him and he’s gone. I never heard him walk away.”

“What do you mean, gone.”

“He disappeared. I called his name. No reply.”

“Lenny, if I heard you right, he pointed to the Luna Moth before it blew up.”

Lenny exhaled a big breath of air. Speaking slowly, he whispered, “Yes. I never told him I was staying there. I eventually get to the Wig Wam and I ask about Red’s Café. The clerk says, ‘Ahh, Red Olson. Really nice guy. He died a couple of years ago. Too bad nobody took over his business.’ Then he asks me if I’m ok. Tells me I look like I’ve seen a ghost.”

“Holy crap, Lenny! You did!”

“For sure, Pete. I did. A ghost that saved my life.”