This historical fiction story was written to the prompt “In peace, sons bury their fathers. In war, fathers bury their sons”, a quote from Herodotus. The fictional characters are Captain Bartlett and Sergeant Boyle. Samuel Wilkeson, Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson, Major Thomas Osborn and General John Buford were present at the Battle of Gettysburg. With two exceptions, all of the dialogue between the characters is fictional. See my notes at the end of the story.

Gettysburg, PA, July 4, 1863

The rain was falling in sheets as Bartlett and his aide, Sergeant Boyle, reined their horses to a stop in front of the Fairview Cemetery gatehouse.

“Ahh, this weather’s manky, sir. Truly ‘tis!” Boyle exclaimed.

Bartlett smiled from inside the hood of his rubber poncho. “Manky. I’ve not heard you say that since Fredericksburg, Sergeant Boyle. This isn’t nearly as bad as that.”

“For sure it’s not Captain. I’m just a tad surly after three days of racing all over this battlefield, dodgin’ every shot and shell the Johnnies could throw at us.”

Bartlett nodded his head in agreement. The horrors he had seen over the past three days left him feeling numb. Gettysburg was not his first battle by far, but it was the most savage one he had been part of. Maybe because they fought to repel an invasion of northern soil. “Sergeant let’s get off these nags and take shelter in the gatehouse arch,” he said.

Under the cover of the arch, they shook the rain from their ponchos like two golden retrievers and tugged off their hoods. From where he stood, Bartlett could see the stretch of the Baltimore Pike toward army headquarters.

Boyle flipped the poncho over his shoulder and pulled a watch from his vest pocket. “When are you expecting the man from the New York Times, Captain, sir?”

“Any minute now.”

“If you don’t mind me askin’, sir, but do ya really think your friend, I mean Mr. Wilkeson’s son, might still be alive?”

Bartlett inhaled deeply and let out a long sigh. “I don’t know, Sergeant. Major Osborn saw Lt. Wilkeson being carried away from his battery. His right leg was gone.”

“Your man, Lt. Wilkeson, is a tough nut, sir. I heard his leg was mangled by a round shot that went through his horse. I heard he used his pocketknife to finish what the cannon ball started.”

Bartlett sighed again and turned his gaze from Boyle to the Baltimore Pike. The heavy rain had lightened to a misty drizzle. Plodding towards them along the Pike was a team of horses hitched to an ambulance. Next to the teamster, Samuel Wilkeson sat bolt upright, shoulders squared, and head held high. His hands rested on his thighs.

“Here they come,” Bartlett told Boylan. He walked out from the cemetery gatehouse to the middle of the Pike and raised his hand to halt the ambulance.

“Good morning, James. To what do I owe the honor?”

He noted Sam Wilkeson’s flat voice before saying, “Sergeant Boylan and I would like to help you look for your son.”

“I would be honored,” Wilkeson’s voice trembled, “And please, sit with me. I need a friend to talk to.”

Bartlett nodded, tethered his horse to the ambulance and climbed aboard and squeezed next to Sam. With a snap of the reins, the wagon jerked into motion and rolled towards town. Sergeant Boylan guided his horse to fall in alongside.

After riding along in silence for a few moments, Sam Wilkeson turned to face Bartlett and said, “Thank you again for offering to help James. But I know where Bayard is. Major Osborn said he was carried to the Alms House after receiving his wound. I suspect he is still there.”

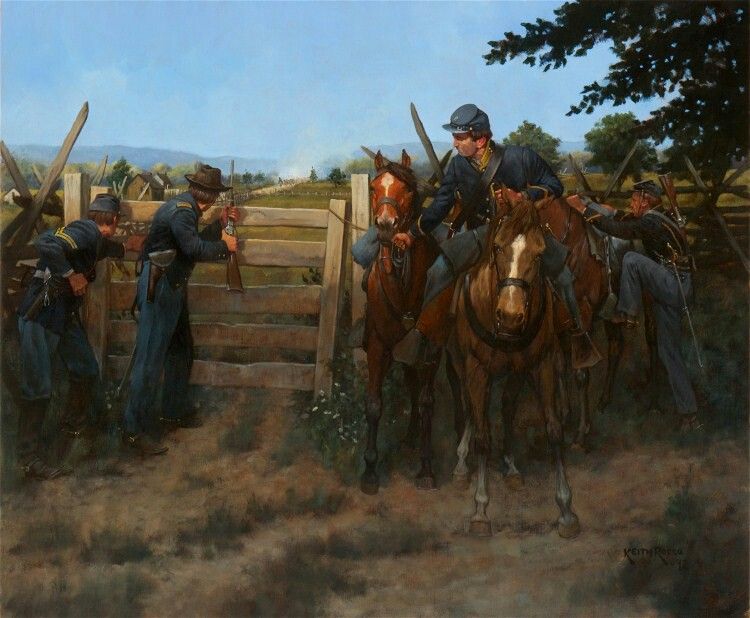

“I know where that house is, Mr. Wilkeson. I saw it early in the morning of July 1st while scouting with General Buford. So, Bayard has been behind Rebel lines for the past three days.”

“Yes. I pray he received adequate care from their surgeons.”

The ambulance rolled slowly along the road through town. Sam Wilkeson spoke again. “James, the survivors of Bayard’s battery told me they were ordered to an exposed area. Rebels were firing on them from three directions. They fought back hard. The Rebs swept the remaining Yankees from the field after Bayard got wounded. He should not have been sent there. Bayard should not…” his voiced trailed off. He let out a long sigh and said no more.

The ambulance passed through town and came to a halt in the yard of the Alms House. Wounded soldiers were everywhere. Bartlett and Wilkeson climbed off the wagon. Joined by Sergeant Boylan, they walked through the door into a den of pure misery. The cries of men being operated on, the sights and smells, were overwhelming.

Bartlett stopped a medical attendant who tried to scurry past them. “Excuse me, this man is looking for his son. He was wounded on July 1st.”

“Name? What’s his name?” The impatient attendant asked.

Sam Wilkeson tried to hide his anger, but it was clear when he spoke, “Lt. Bayard Wilkeson. Battery G, 4th U.S. Artillery.”

“Don’t know him.” The attendant pulled free from Bartlett’s grasp and hustled off.

“Sir, we know where your son is.” The soft voice startled the three men, and they turned to see two young women approaching. “We took care of him after he was brought here.”

Wilkeson’s shoulders sagged. “Cared. You said cared.”

“Yes sir. We’re sorry, he passed on the evening of July 1st. We stayed by his side to the end.”

His voice was heavy with emotion, Wilkeson asked, “Where is he? Can you take me to him?”

The women led him out of the building to a mound of dirt beneath a tree. Bartlett and Boylan trailed along. Wilkeson stared at the ground where his son rested. Falling to his knees, he placed his hand on the grave and cried out in anguish, “He was only 19 years old! Dear God.” Sam Wilkeson sobbed.

Boylan looked away and noticed Bartlett wiping tears from his face. Tossing aside regulations, he laid his arm over his commander’s shoulders. “I’m profoundly sorry for the loss of your friend, sir. I truly am. He was a fine man.”

“Thank you, Sergeant Boylan. We will miss him forever. Like so many in this war. Now he sleeps the sleep that knows no earthly waking.”*

Boylan turned his gaze back to the scene at the grave. “‘‘Twas it Herodotus, sir? Who said ‘In peace, sons bury their fathers. In war, fathers bury their sons.”

“It certainly was,” replied Bartlett. Patting the sergeant on his back, he said, “Let’s see what we can do for Mr. Wilkeson.”

Notes

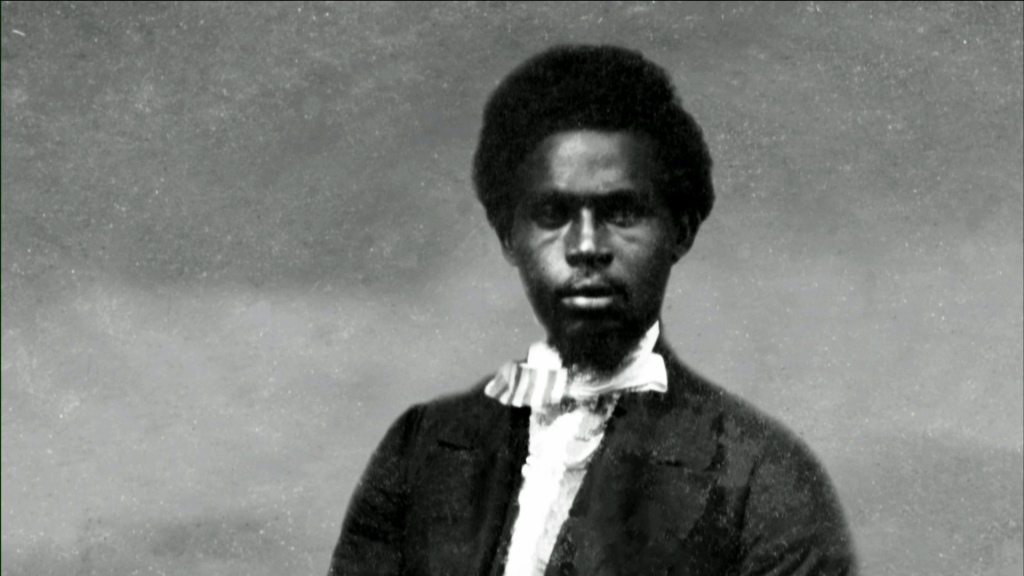

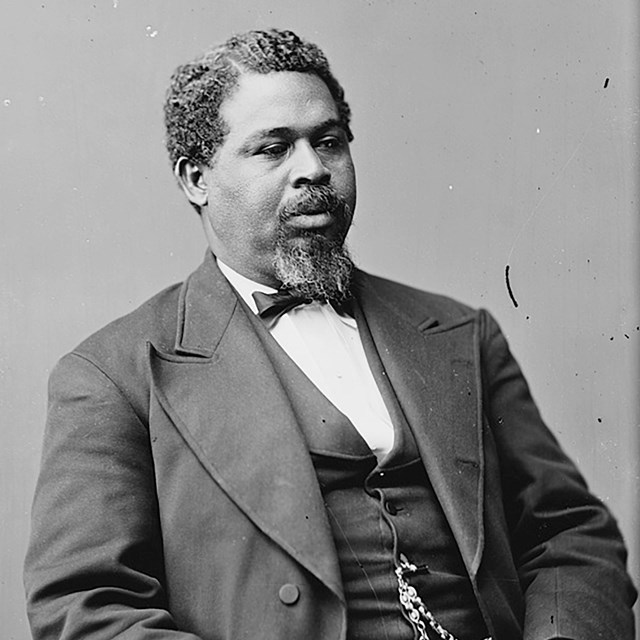

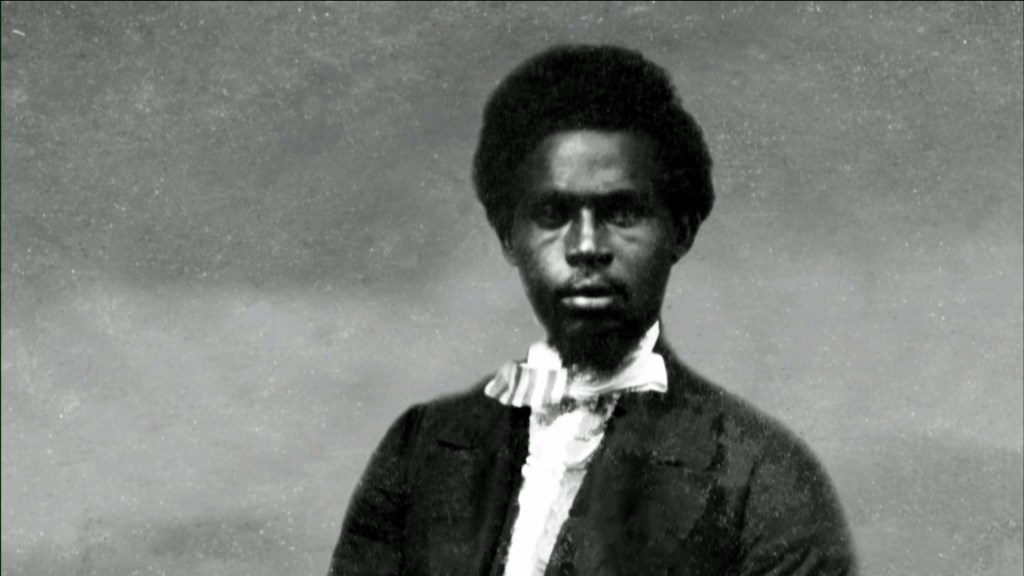

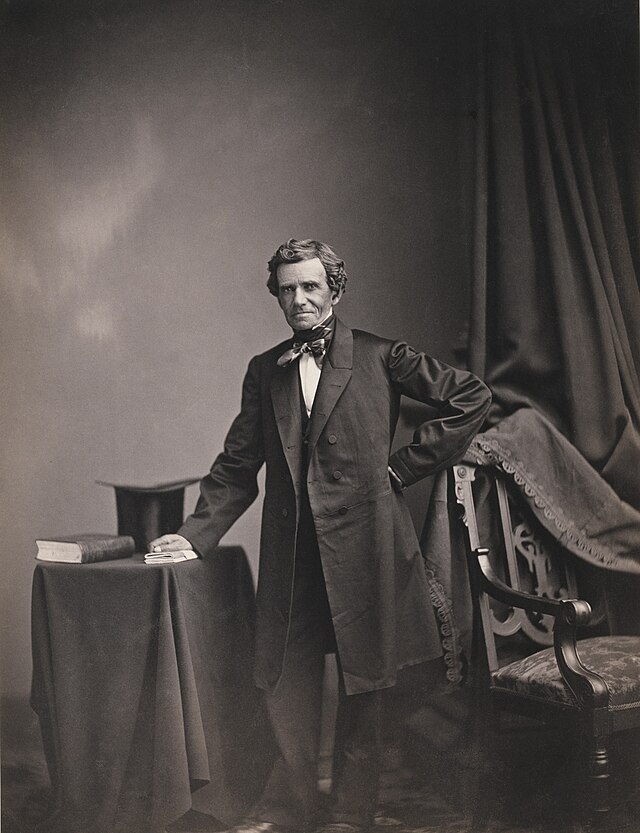

1) The Wilkeson’s were a prominent family from western New York. Samuel Wilkeson’s father was one of the founders of the city of Buffalo and his wife was the sister of suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. After working for Horace Greeley and the New York Herald, Sam Wilkeson joined the New York Times as a war correspondent and was reporting on the battle of Gettysburg when he learned of his son being wounded on the morning of July 1st.

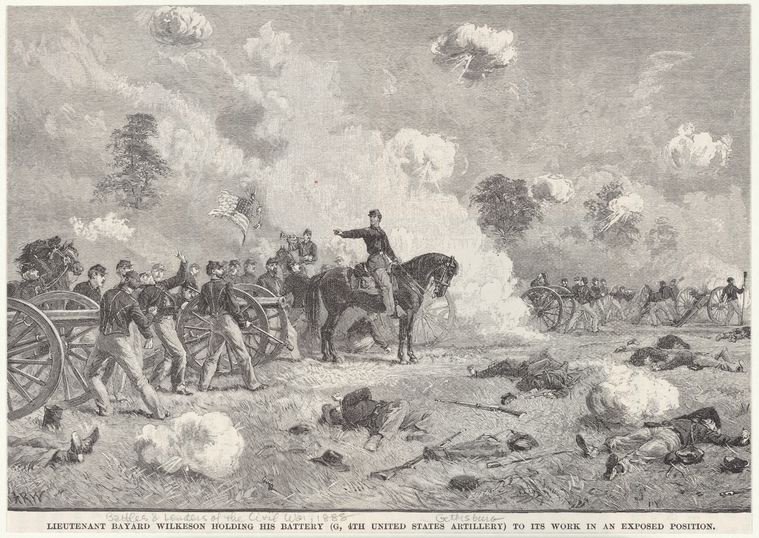

2) Nineteen-year-old Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson was a rising star in the Army of the Potomac and led Battery G, 4th U.S. Artillery. On the morning of July 1, 1863, his battery wreaked havoc on the Rebels advancing on the town of Gettysburg. So efficient was his leadership, Rebel artillery commanders ordered their gunners to aim directly at the young Lieutenant, prominently exposed on horseback. An artillery round struck the horse, passing through it and mangled Bayard’s right leg. He used his pocketknife to sever through the couple of tendons still connected to his leg. Carried to the county poor house, he died from shock and loss of blood the evening of July 1st.

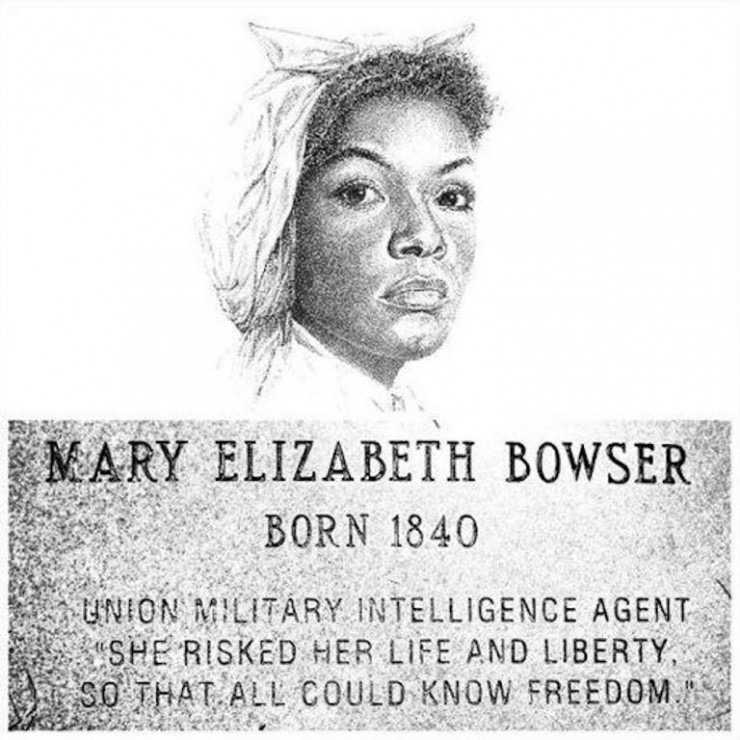

3) The words, “sleeps the sleep that knows no earthly waking” were not spoken by my character, James Bartlett. They appeared in a letter of condolence written to Samuel Wilkeson by Eunice Beecher. Eunice was the wife of noted minister, orator, and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher. Her sister-in-law was Harriett Beecher Stowe.