It was late afternoon, Saturday 2 May 1863. The men of Colonel Leopold Von Gilsa’s Brigade (in Charles Deven’s Division, 11th Corps, Union Army of the Potomac) were at ease. Assigned to hold the far right of the Union line, the 11th Corps was positioned on the Orange Turnpike, near a tavern called Dowdall’s, in a densely wooded area, named “The Wilderness” by the locals. Von Gilsa’s Brigade was the last unit in the Union line, nothing to their right but The Wilderness thickets. It was rumored that Robert E. Lee’s Army of the Northern Virginia was seen to be retreating. Union regiments had tangled with some elements of Stonewall Jackson’s Corps marching along a road in a direction away from the Union lines.

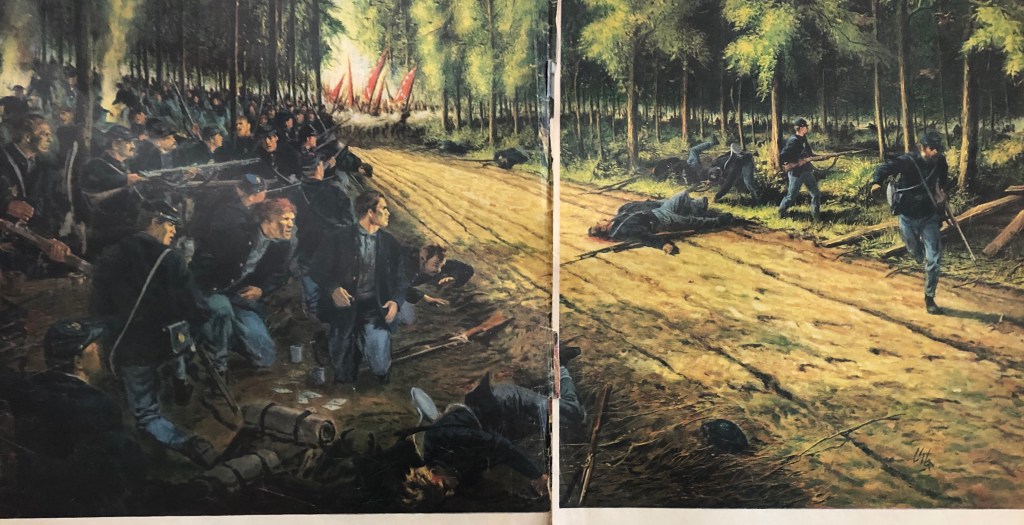

With that knowledge, Von Gilsa’s men were relaxed with rifles stacked, coffee boiling over campfires, eating and playing cards. At about 5:15 P.M., deer began to bolt from the woods into Von Gilsa’s camps. The Yankees tried to catch them in the hopes of having a venison dinner. The leaping deer were soon followed by rabbits and turkeys. The screeches of birds filled the air. The loud bark of a cannon and the “whicker whicker” sound of a passing artillery round made the Yankees stop their activities. The round flew down the Orange Turnpike and exploded over Von Gilsa’s headquarters. The next sound to burst from the woods was the high pitched sound of the Rebel Yell being screamed by thousands of Confederate soldiers. The Wilderness erupted in flame, Von Gilsa’s startled men were bowled over by the volley. Those not shot dropped their cards and kicked over coffee pots in their mad scramble to get their rifles. The Rebels were not retreating! They were attacking!

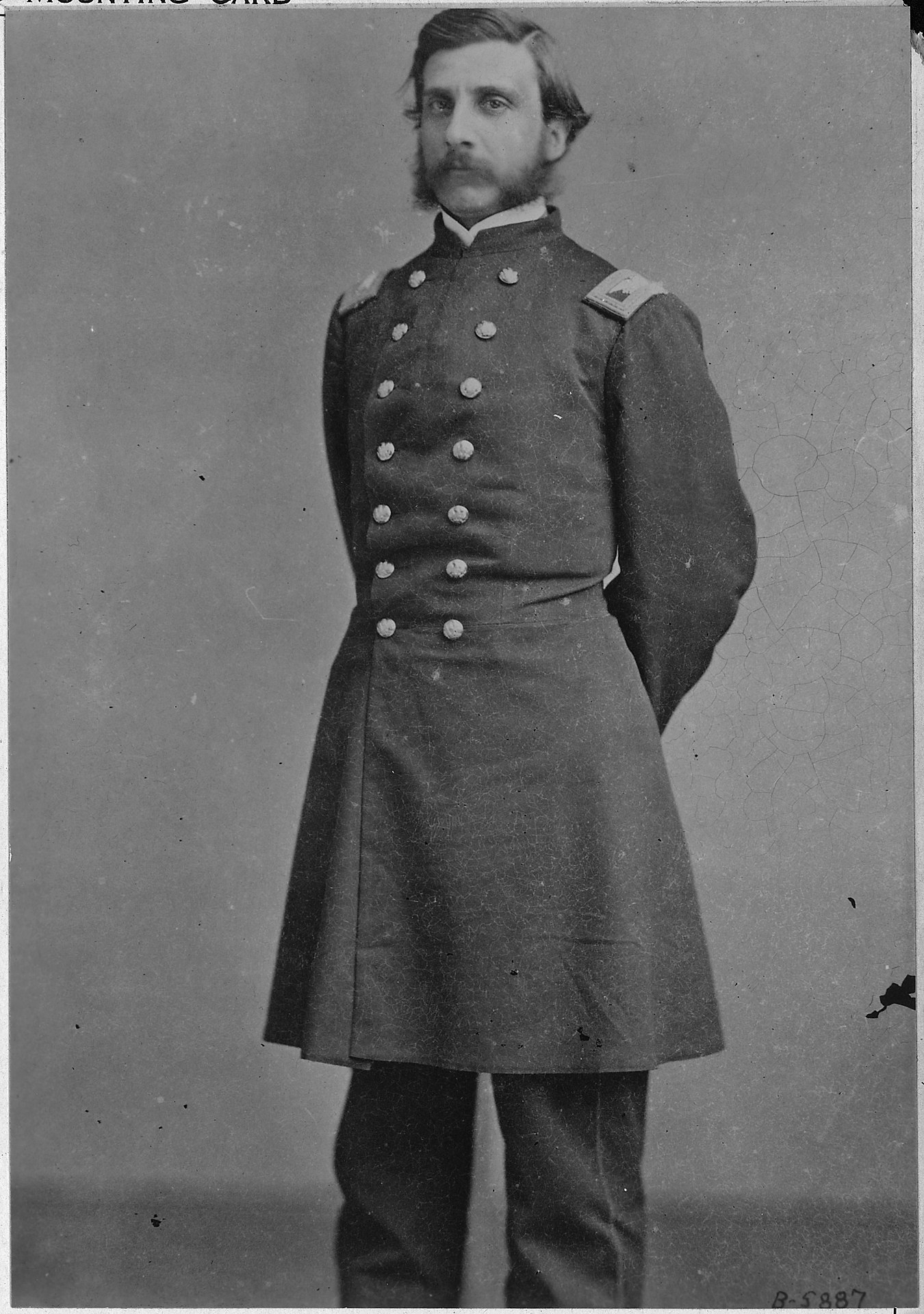

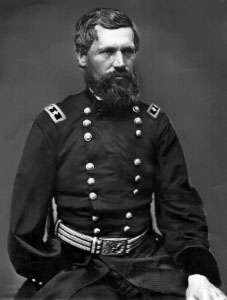

Lee’s army was not retreating. Jackson’s column, that had appeared to be marching away from the Union lines had, actually been on a long route that took them to the unsupported Union right. Jackson’s entire Corps, 26,000 men, flowed from the Wilderness like lava and overwhelmed the Union Regiments. The shattered remnants of Von Gilsa’s Brigade rushed pell mell into the other brigades of the 11th Corps, followed closely by Jackson’s howling troops. Attempts to form a defensive line to slow Jackson’s hordes were swatted away like flies. The Yankees began to break for the rear in a panicked rush. Jackson’s charge was rolling up the Union 11th Corps like a rug. The one-armed commander of the 11th Corps, General Oliver Otis Howard, with a flag stuck under the stump of his right arm and a pistol in his left hand, tried to set an example in an attempt to organize a resistance.

Howard’s efforts to rally his Corps were unsuccessful. Throwing aside rifles, packs, anything to lighten their load, the men of the 11th Corps continued their mad dash to the rear. The path of their flight was leading them to Chancellorsville, a small gathering of homes dominated by the Chancellor family mansion. The Chancellor house was now the headquarters of Union General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Union staff officers had been paying close attention to the sounds of battle drifting from the 11th Corp position. Peering intently at a rising cloud of dust approaching the Chancellor house, a keen eyed staff officer suddenly shouted “My God! Here the come!”. All was pandemonium at the Chancellor House as officers scrambled to stop the flight and organize a defense. Troops from other units were plugged into the line and artillery was wheeled into position. Dusk was beginning to form and the combination of falling darkness and stiffening Yankee resistance finally slowed Jackson’s assault.

Only 3/4 of a mile from Union Army Headquarters, Jackson desperately wanted to renew his assault. He was willing to risk an night time battle and while scouting possible attack approaches, was accidentally fired on by his own men and mortally wounded. The evening of May 2, 1863 would be hellish. The fighting during the day had started fires in the Wilderness woods. Wounded soldiers calls for help would soon turn to screams as the flames would overtake them. Any movement in the dark woods would cause an eruption of wild shooting.

Stonewall Jackson was already a legend by the time the Battle of Chancellorsville was fought. However, his audacious assault on the 11th Corps and near capture of Union Headquarters would be the crowning jewel of his career. After his wounding, he was hurried to the rear and his arm was amputated. Although it initially seemed that Jackson would recover from his wounds, he contracted pneumonia and died on May 10, 1863.

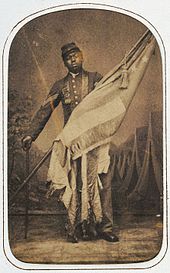

At the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Union 11th Corps was held in low regard. The unit was plagued by morale problems and was a recent addition to the Army of the Potomac, being transferred from another department. Almost 2/3 of the organization were European immigrants, officers having names like Von Gilsa, Buschbeck, Schimmelpfennig, Schurz. The prejudices of the times led to mistrust of their abilities as soldiers. The 11th Corps would also be driven from the field at Gettysburg, forever being named “The Flying Dutchmen” after that.

Notes: Back in the day, I used to give a presentation on the Chancellorsville Campaign to Civil War Roundtable groups and schools in Connecticut. It was in the days before laptop computers and PowerPoint, so I had big flip chart maps and overhead projector transparency sheets.

I have visited the Chancellorsville battlefield a few times and drove the path that Stonewall Jackson marched to launch his flank attack on the Army of the Potomac. That was many years ago and at the time it was still a narrow dirt road that wound through Wilderness.

sources: Ernest B. Furgurson, “Brave Men’s Souls, Chancellorsville 1863”; John Bigelow, “The Chancellorsville Campaign” (this is the Gold Standard of all Chancellorsville books); issues of Blue & Gray and Civil War Times Illustrated magazines that relate to the Chancellorsville Campaign.