Storm clouds darkened Washington D.C. in December of 1862. The clouds were not formed by any weather or atmospheric conditions, rather they were formed by despair, partisan rancor, fear and loss of confidence in the U.S. Government’s ability to achieve a victorious end to the war that was about to enter its 3rd year. The cause of all of this turmoil was the defeat of the powerful Union Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Fredericksburg by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia on December 13. Union commander, Major General Ambrose Burnside, sent his magnificent army of 122,000 men on a series of futile frontal attacks in an attempt to overpower and defeat the 80,000 Rebels under the command of General Robert E. Lee. Once that was accomplished, Burnside would push to capture the Confederate capital city of Richmond. Lee had other ideas and defeated Burnside in what was, perhaps, the most lopsided victory in the Civil War. For the balance of 1862 and into the start of the new year, the blame storming emanating from local, state and federal government officials, as well as northern newspapers would result in calls for the impeachment of President Lincoln and for several cabinet members to submit letters of resignation. Lincoln, of course, was not impeached and he did not accept the resignation letters. But now all eyes were on Ambrose Burnside and the Army of the Potomac.

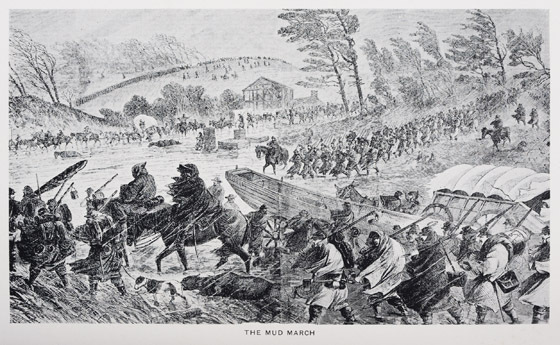

The Mud March

After his bloody defeat at Fredericksburg, General Burnside was determined to attempt another advance on Richmond. After vetoing one plan, Lincoln gave the nod for an alternative one and Burnside began his preparations. Winter campaigns during the Civil War were perilous ventures. The lack of any methods to accurately predict weather conditions could wreak havoc on the movements of armies. Freezing temperatures and snow fall could, and would, change to slightly warmer days with heavy rains. With nearly all roads being dirt, wet weather could make those roads almost impassable.

After sunny days with temperatures above freezing and roads in reasonably good shape, Burnside issued orders early in the morning of January 20, 1863 to begin the movement towards Richmond again. With regimental bands playing “The Girl I Left Behind Me”, the mighty Army of the Potomac marched out of their camps, although not starting until 11:00 AM. By the evening of January 20th, the leading elements had marched 12 miles, stopping just short of Banks Ford on the Rappahannock River. As darkness fell, the soldiers stacked arms, pitched tents, and cooked their suppers. While preparing to turn in for the night, a light rain began to fall. By midnight, the full force of an unexpected Nor’easter blew across northeast Virginia. The overnight torrents of rain flooded tents and campsites. The soldiers suffered miserably through the night as the cold rain soaked their heavy wool uniforms. The curtain of night lifted on January 21st to reveal a tableau of misery. The rain fell in sheets from a sky that was steel gray. Worse, the roads had become quagmires. Wagons, cannon and caissons sunk into mud that was hub deep and became stuck. Teams of horses and scores of soldiers could not get them unstuck. Trees were cut down and laid in an attempt to “corduroy” the roads and make them passable, but they were consumed by the quagmire. Mud oozed into boots and shoes or sucked them completely off the soldiers feet, lost forever. Streams and rivulets became raging rapids, the Rappahannock River rose and became too deep and swift to try and wade across Banks Ford. Pontoons were ordered up to bridge the Ford.

(The tune struck up by the regimental bands as they broke camp on 20 January 1863):

Shortly after breakfast on the 21st, Burnside and 3 members of his staff left his headquarters to check on the progress of his army. Burnside’s spirits began to flag as he passed pontoon trains mired in mud, unable to be pulled free by 100 soldiers and teams of 24 horses. Moving on towards Banks Ford, he passed more signs of misery, observing exhsusted, mud covered soldiers sitting on the roadside, indifferent to the torrential rains. The partially submerged carcasses of horses and mules who collapsed and drowned in the swampy roadways gave gruesome evidence to the toll paid by the animals trying to keep an army moving. Only three pontoons had made it to Banks Ford. Confederate soldiers could be observed on the other side of the Rappahannock, gleefully watching the Yankees wallowing in the mud. All elements of surprise were dashed. Burnside dejectedly rode back to his headquarters. Arriving shortly after 5:00 PM, he telegraphed the War Department in Washington D.C. with the information that heavy rains had delayed his progress. Government officials took note of this ominous report and sensed another failure in the making.

The Army of the Potomac spent another miserable night and awoke on January 22nd to the unrelenting rains. Rebel sharpshooters began to pepper the soldiers guarding the pontoons. Other Confederate wags had posted signs saying “Burny in Mud” and “This Way To Richmond”. Painted in huge white letters on the roof of a barn on the Rebel side of Banks Ford were the words “Burnside Is Stuck In The Mud”. With no chance of success, Burnside called off the advance. The soldiers turned around to return to their camps. This did not end the misery by any means, it was still pouring with “Mud, mud, mud. Everywhere mud”. On 23 January 1863, an exhausted and demoralized Army of the Potomac arrived back where they started, 3 miserable days earlier. The Official Reports of this action would refer to this as “The Mud March”, and 158 years later, it is still called “The Mud March”. On 25 January 1863, Ambrose Burnside was replaced by his bitter enemy, the conniving Major General Joseph Hooker, as commander of The Army of the Potomac.

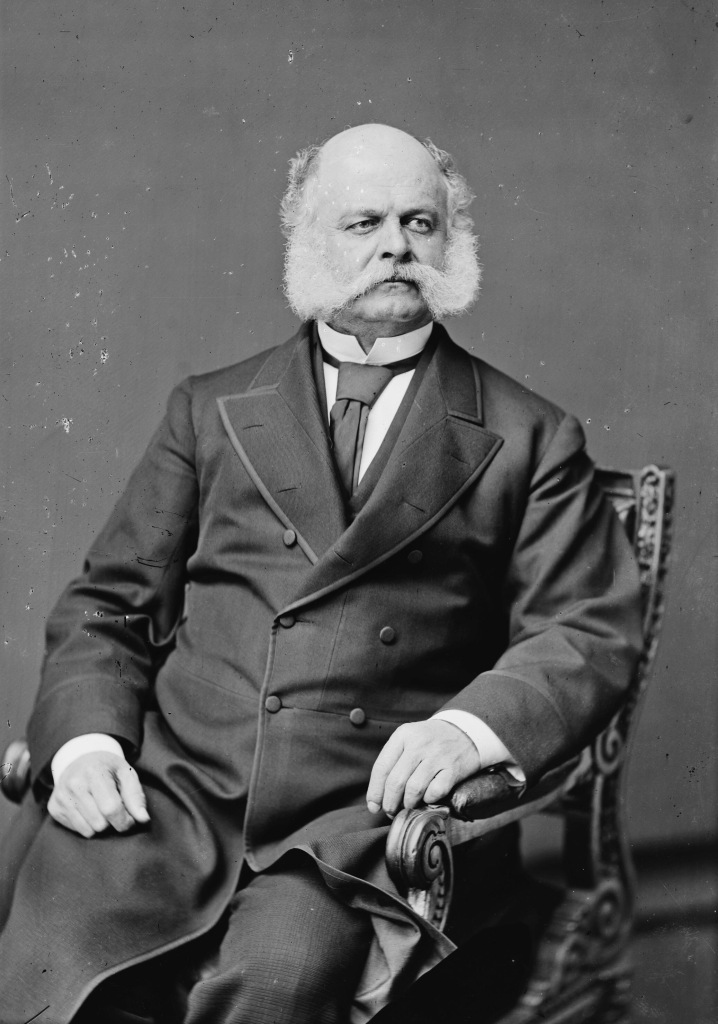

Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside was born in Indiana in 1824. Attending the United States Military Academy at West Point, he graduated in Class of 1847, ranking 18th out of 38 students and was assigned to the artillery. After service in the Mexican War and on the Great Plains, he resigned and moved to Rhode Island. Inventing a breechloading rifle – The Burnside Carbine – he opened a factory in Bristol, Rhode Island to manufacture them. Treasurer of the Illinois Central Railroad when the Civil War began, he resigned to become Colonel of the 1st Rhode Island Volunteers. Because of his prior military service, Burnside was promoted to Brigadier General and led a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run. Tall, outgoing, likable, impressive, Burnside’s Civil War career was up and down. He showed flashes of competence, in smaller scale Campaigns he led in Eastern Tennessee and along the North Carolina coast, but when he performed badly, he performed really badly. He was involved in two of the biggest debacles in the Civil War, the Battle of Fredericksburg and the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, Virginia in 1864. Burnside admitted, many times, that he was not qualified to lead an army and had twice rejected the offer to command the Army of the Potomac. After the war, Burnside returned to Rhode Island where he served 3 terms as Governor before getting elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served until his death in 1881. His outstanding physical characteristics were his bushy, mutton chop whiskers which are still called to this day “Sideburns”. You will see in the following photo:

Sources:

“Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!” By George C. Rable. An excellent history of the Fredericksburg Campaign. “The Civil War Encyclopedia” compiled by Lt. Col.Mark Boatner. Several back issues of The Blue & Gray and Civil War Times, Illustrated relating to the Fredericksburg Campaign and The Mud March.

William Marvel wrote a biography of Ambrose Burnside, which I have, but I found it somewhat disappointing. Marvel tries to pin Burnsides failures on others. While there are many facts that point to Burnside being undermined by uncooperative subordinates, much of the blame does rest with him.

Great story, I felt like I was there.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very enjoyable read

LikeLiked by 2 people

Always welcoming your great “tidbits” from the Civil War. Keep them coming!

LikeLiked by 1 person